There are “saws” and “drifts” and assorted notions that Walter Hill refers to in conversation, anything to keep from sounding like “a pedantic old fucker that should be put on the shelf someplace.”

As he reflected over a career in film and television that led to his selection for this year’s Laurel Award for Screenwriting Achievement, the much-honored writer-director returns to one such saw: if you get the craft good enough, that makes the art.

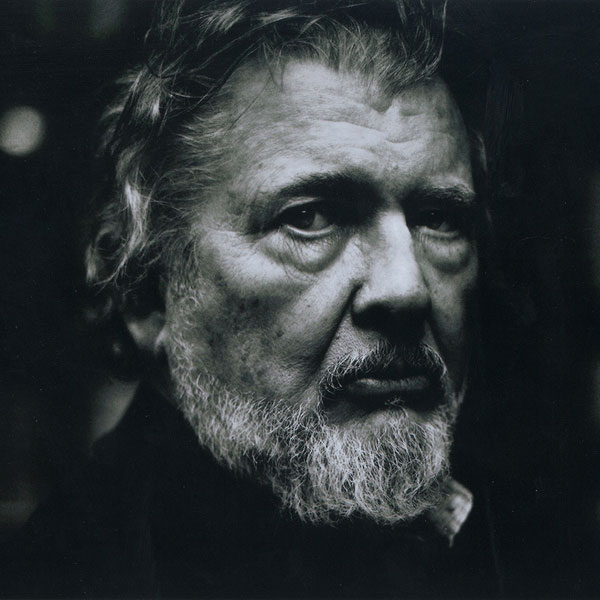

Walter Hill. Photo by Nicolas Aproux.

Walter Hill. Photo by Nicolas Aproux.“Screenwriting is strange,” Hill told Written by in a recent interview. “Screenplays are not novels. They’re not plays. People like to think there are accommodations in both, but I don’t think that’s terribly helpful. I think they kind of have a form of their own. It’s kind of an unrecognized form of literature.”

Mulling over the craft of screenwriting, Hill returns to a bit of wisdom provided by his late friend and longtime writing partner David Giler, with whom he collaborated on Southern Comfort, Aliens, and Undisputed among others.

“He said it’s a strange form of literature in that the only people who read these scripts are the people who are going to destroy them,” Hill said of Giler who died in 2020. “He was a fascinating guy and a lot of fun to be around. I miss him dearly.”

Moving across artistic genres from tough guy action films to detective tales, from the science fiction worlds of Alien through his much-beloved westerns, Hill’s work has, in the words of WGAW board member Scott Alexander “completely changed the screenwriting game.”

“Before him, scripts were just dialogue and prose. Walter showed us that scripts could be visual,” Alexander said. “He uses carriage returns and quick ideas to be punchy. He wants the reader to experience the dramatic moments the way the viewer will. They’re lively. Audacious. Visceral.”

For his part, Hill reflects on his works with a mixture of self-effacement and appreciation that the critical appreciation of such films as Hard Times, The Driver, and The Warriors continues “and usually in a positive way.”

“You’d like to think you did something right over the years. Nobody wants to pick up the paper and read that you’re a bum,” he said, “but that’s just part of the business if you’re going to be around for awhile and have a serious shot at a real career. It’s an up and down business. That’s part of the deal.”

Earning the Screen Laurel award qualifies as an “up.” Hill says he is pleased and somewhat taken by surprise. “I used to read about the Laurel. Given the end of the street that I work on, I thought I’m never going to be up for that one,” Hill said. “It shows you how wrong you can be. And pleased.”

With my stuff, I always thought you could make a movie out of it. Whatever faults it had in other areas, you could always make something out of it that would be coherent.

- Walter Hill

The same holds true for being a WGAW member, says Hill, who felt a huge sense of accomplishment when he got his card in 1970. As a union member, the man who said he had “joined the circus” when he entered the business was now—as a WGAW member—no longer relegated to clearing the peanuts out of the elephant cage.

A lifelong lover of movies, Hill—a Long Beach native—took an interest in the art form while an undergraduate in New Mexico and Michigan. Moving back to Los Angeles, he worked in production for several years while writing on the side.

The problem, Hill realized, was that he could never finish any of his scripts. So he buckled down, took time off from his production work and finally completed a script…which he promptly threw away. Then he wrote another, a western which got optioned, was not produced, but still garnered Hill some attention.

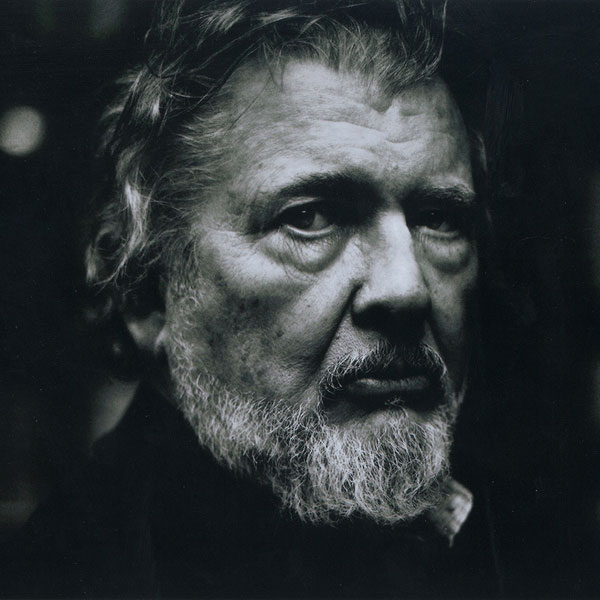

Walter Hill on the set of 1979's The Warriors.

Walter Hill on the set of 1979's The Warriors.“It was called Lloyd Williams and His Brother. Maybe that was one the reasons it didn’t get made,” Hill said. “Years later, Sam Peckinpah was talking about doing it right after we did The Getaway.”

Hill was part of an unofficial writers’ program out of Warner Bros. that included Giler, John Milius, and Terrence Malick. Hill’s first produced script was the original detective story Hickey & Boggs, followed by The Getaway.

“That was an enormous commercial hit, and that put me in a different way in the business,” Hill said. “There are writers who want to sell, there are writers who have credits and then there are writers who have hits and credits. I sort of sped through the process, and it took a while for me to get it down, I guess.”

He corrects himself. “You never get it down, but I always had an instinct for structure. People send you scripts and a lot of them, even if you like them, you couldn’t shoot them. With my stuff, I always thought you could make a movie out of it. Whatever faults it had in other areas, you could always make something out of it that would be coherent.”

Hill made his directing debut with Hard Times in 1975, and has gone on to direct nearly 30 film and TV features up through 2022’s Dead for a Dollar. Accolades include Emmy Awards for producing Broken Trail, for directing the pilot of Deadwood, and the Cartier Glory to the Filmmaker Award at the Venice Film Festival in 2022.

As a writer, he has penned original scripts and rewritten scripts both with and without the original writer. “So I guess I’ve touched every base that screenwriting puts up,” Hill said.

“It’s an odd way to make a stance as a writer,” he continued, “because nobody goes out and rewrites someone else’s novel. Usually nobody goes out and rewrites somebody else’s play. You don’t paint over some painter’s art.”

“With screenwriting, it’s just part of the game,” he added. “You write. You’re going to be rewritten. You rewrite. It’s just part of the deal.”

As the interview wraps up, Hill reflects again Giler, his former business and creative partner, and “bon vivant.”

“I was thinking that so many of the things that I wrote, that I’m credited with writing, he co-wrote,” Hill said. “I wish he were here for this. He’d say, ‘Where’s mine?’”