President Mary McCall Jr. was a pioneer in Hollywood who fought for the rights of all writers.

1/23/2026 • Evan Henerson

His Name is Reo and He Can Spin a Tale

2026 TV Laurel Award Honoree Don Reo reflects on his career.

President Mary McCall Jr. was a pioneer in Hollywood who fought for the rights of all writers.

On the evening of November 12, 1942, the Screen Writers Guild held its annual election of officers. Forty-two men and women stood as candidates for the executive board; of these, eleven were elected. The candidate for president ran unopposed: Mary C. McCall Jr.

She had been an active member of the Guild since its formation 10 years before. “As soon as I came to Hollywood,” she explained in an interview, “I went and joined the SWG… I believe very strongly in the necessity of a strong writers’ union, not only for the financial benefits which can be obtained by collective bargaining, but also for the professional advantages.”

McCall would serve a total of three terms as SWG president, and twice as acting vice-president. She served multiple times on the executive board as well as on the Board of Governors of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Mary McCall, Jr. was a woman whose petite physique masked a take-no-prisoners commitment to collective bargaining

Mary McCall, Jr. was a woman whose petite physique masked a take-no-prisoners commitment to collective bargainingIn her debut speech as president in 1942, McCall did not draw attention to herself as the first female head of the Screen Writers Guild. Instead, with characteristic diplomacy, she began with a list of male colleagues who were now “in service” overseas or in intelligence work. She stressed the collective responsibility of writers at home and abroad. “To all of us,” she said, “the war has brought a heightened sense of responsibility.”

Although some Guild members, remembering the heavy-handed propaganda of the First World War, were worried about the potential for government censorship and manipulation, McCall declared, in this war, “the ideas are ours...The pictures we write will be better pictures, more entertaining, more exciting, and quite possibly more profitable, because the war has demanded from us that the screen shall not be used to tell vapid stories, meretricious stories.” Bad writing was false writing, whether it was heavy-handed propaganda or escapist fare. “The strengthening of the ties of brotherhood between nations accomplished by good screenwriting, points up the lesson we've got to learn.”

McCall continued, “Screenwriters have in their hands a weapon not only mightier than the sword—it’s mightier than the Garand rifle. It’s our job to see that it is trained always on the enemy, that its fire never wounds one of our own.”

She was well aware that over the past decade, the Guild’s enemies had been the heads of the studios and the producers. As an executive board member, she had served on numerous committees and meetings with producers who saw the writers’ efforts to improve pay and normalize working conditions as the end to executives’ control of the studio system. But now, after years of struggle, McCall could say confidently that the union contract guaranteed by the New Deal’s National Labor Relations Board was in place and changing the status of writers across the industry. That contract forced pay from $40 to at least $125 a week. “It’s become almost natural for writers to use the front stairs,” she joked. The agreement not only raised wages and flat-price deals, it gave “protection from having our brains picked by predatory producers.” But a contract was only as good as the members who uphold it: “You must not let yourself be cajoled, wheedled, browbeaten, coaxed, kidded or stalled into speculative writing…Every member can help the Guild live up to the contract, every member can help the Guild see to it that the producers live up to the contract.”

She ended the historic speech with this: “By nominating me unopposed for the Presidency of the Guild you have given me the greatest honor which I’ve ever received. I’ll work hard for you.”

Always succinct, always good for her word, and always politic, McCall was a master negotiator with producers. A woman whose petite physique masked a take-no-prisoners commitment to collective bargaining, McCall was the Guild’s most valuable asset from its earliest days through the blacklist. Eventually, she would publicly sacrifice her career in Hollywood defending the basic right of screen credit against a new breed of politically repressive producers. But, like her most famous screen creation, Maisie Ravier, Mary C. “Mamie” McCall Jr. did not give up on herself or her show business industry. Sadly, she’s never received the screen credit she deserves.

Writer & Fighter

Mary McCall, Jr. with a figurine of her most famous screen creation, Maisie Ravier. Photo: Dwight Franklin

Mary McCall, Jr. with a figurine of her most famous screen creation, Maisie Ravier. Photo: Dwight FranklinIt usually surprises people to learn that women writers thrived in studio-era Hollywood and that McCall even existed—let alone ran the Guild in 1942-43, 1943-44, and 1951-52. Hollywood has often been portrayed as a repressive patriarchal corporate system intent on disempowering women (particularly after 1930), with more than one historian claiming that the studio era saw women lose the creative control they earned in the silent era. Although the number of female directors certainly declined (to basically just Dorothy Arzner), it wasn’t the same for all branches of the industry. In many ways, Hollywood remained a pioneer among major industries in women’s employment, leading McCall’s lifelong friend Bette Davis to reminisce in 1977 that “women owned Hollywood for 20 years [1930-1950], and we must not be bitter.”

Mary C. McCall Jr. was one of a number of young women to arrive in Hollywood in the early 1930s with a college degree. She came from a wealthy New York Irish American family. Her father Leo McCall was the son of John McCall, the former president of the New York Life Insurance Company, and her mother Mary Burke was a well-to-do debutante pretty enough to have had her portrait painted. Young McCall grew up in comfortable Englewood, New Jersey (an only child until her teens), and she was determined not to follow in her mother’s footsteps. As she recalled, “From the time a composition of mine written in first grade was well received by the teacher and even most of the kids, I had had only one ambition—to be a professional writer.”

Though hard times had pinched the family finances, her father budgeted enough money to educate her until she was 22. McCall wanted to attend a women’s college, and went to Vassar where she edited the college newspaper, studied English and political science, and graduated at 21, a self-styled “big wheel” on campus. While in a post-graduate study program at Trinity College Dublin, an up-and-coming Foreign Service officer from Massachusetts tried to marry her, but, as she recalled with a sigh of relief, “fortunately for me this romance broke up in ’27.”

Although she married costume designer Dwight Franklin (The Black Pirate, 1926) the following year, McCall remained career focused. She returned to New York and worked in an advertising agency concocting snappy copy, writing short stories, and eventually two novels. Her first book, The Goldfish Bowl (1932), was serialized before publication, and, as it was loosely based on her old friend from Englewood, Elizabeth Morrow, her sister Anne, and Charles Lindbergh, the book attracted the attention of Hollywood, Warner Bros. bought the rights.

From the time a composition of mine written in first grade was well received by the teacher and even most of the kids, I had had only one ambition—to be a professional writer.

- Mary McCall

Though McCall would always be miffed that Darryl F. Zanuck didn’t hire her to adapt It’s Tough to Be Famous (Robert Lord got the assignment), she landed a 10-week job at Warner Bros. writing Street of Women (1932), “a dog” of a picture the studio undoubtedly thought was more suitable material for a new female writer. With new-born daughter Sheila in Arizona with her grandparents and Franklin back East for much of the time, she stayed in Hollywood long enough to have an affair with the star of her picture, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., and see the screen adaptation of her novel enjoy a good preview.

But “at breakfast…I saw a newspaper with banner headlines: ‘Lindbergh Baby Kidnapped.’ My first thought was of Anne, but my second thought, I admit, was: ‘There goes the book!’ And how right I was! The big bookstores said they would stock it in case anyone asked for it, but they certainly would not feature or promote it in any way, since, as a satirical comedy, it was in such execrable taste, with the Lindberg family undergoing such suffering.”

McCall sold another book to the studio for Fairbanks, a tragic Russian Revolution love story called Revolt (later retitled Scarlet Dawn, 1932), but though the film was action-packed and displayed the star’s aristocratic good looks, it didn’t lead to any immediate studio offers for the author.

McCall and Franklin returned to New York. She continued to add to her writing profile, publishing stories in Colliers and other “slick-paper magazines.” But the Depression soon convinced the couple that “more and better paid employment for both of us lay in Hollywood.” In early 1934, they relocated permanently to the West Coast, taking four-year-old Sheila and her governess Josephine Prickell along.

Mary returned to Warner Bros., this time with a long-term writing contract, and became active in the Screen Writers Guild, working to increase membership and develop a contract with the producers which would guarantee a minimum wage for all (including script readers), unemployment compensation, credit arbitration, and the right to strike.

A Balance of Public and Private

Adapted from the short stories by Nell Martin, McCall’s Maisie Ravier franchise about a brash yet lovable brooklyn showgirl made actress Ann Sothern a star

Adapted from the short stories by Nell Martin, McCall’s Maisie Ravier franchise about a brash yet lovable brooklyn showgirl made actress Ann Sothern a starThrough it all, she remained Mary C. McCall Jr. She and Dwight Franklin had a sound, equal partnership that was based as much on mutual respect for each other’s intellect and talent as on physical attraction. She never stopped working after marriage, and it was Franklin who had encouraged her to go back to writing short stories to escape the boredom of her advertising job. When they married in 1928, she presented him with a “Sonnet for a Partnership,” expressing her view that even in love, women and men had to preserve their equality and individuality.

Because there was a 16-year age gap between them, McCall benefitted from Franklin’s knowledge of Hollywood as much as from his amused detachment from the glitz of Southern California. Franklin needed perspective, particularly when McCall had affairs with Fairbanks and later Leslie Howard, but he loved her and tolerated what was—even by Hollywood standards—a very modern, open marriage. (Years later in the supposedly straight-laced 1950s, McCall would discuss the benefits of pre-marital sex, reasoning that, “Before you buy the shoe, you have to try it on first.”)

A number of prominent female screenwriters in the 1930s had well publicized relationships with other writers (Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett, Tess Slesinger and Frank Davis, Dorothy Parker and Alan Campbell, Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett), but these partnerships were focused on their shared careers as writers. Mary was unique in being married with three (and, from 1944, four) children for the most productive period in her career, something that very few working women in Hollywood dared—or were allowed—to do. Her friend Louella Parsons, a big fan of McCall’s Maisie series for MGM, reported McCall’s career successes, remarriages, and new children with equal measures of praise and admiration. Things were not so easy for other women in Hollywood. Studios often forced women to choose between furthering their career and building their family. Her close friend Bette Davis, whom McCall first met when they were dissatisfied workers at Warner Bros., only became a mother late in her career as the studio’s top star (1947) and would terminate her contract in 1949.

But in the early 1930s, Mary came closest to having it all as a woman in terms of public career and private life. During the early years of her marriage, she wrote or worked on half a dozen scripts for Warner Bros., including a sweet May-December romance for newcomer Jean Muir (the future television blacklistee also starred in McCall’s Midsummer Night’s Dream), two hot Code-bending stories for Barbara Stanwyck (The Woman in Red and The Secret Bride), and a prestige adaptation of Sinclair Lewis’s Babbit. She was at the studio all day, and little Sheila was with her governess.

At night, instead of reading bedtime stories, she was either attending or hosting Guild meetings, many of them in the McCall-Franklin home. When she was hard at work writing the script for A Midsummer Night’s Dream (starring her old New York Irish pal, James Cagney, as Bottom), she was very pregnant with twins. Years later, she described it simply in a collection of reminiscences intended for her children: “Gerald McCall Franklin and Alan McCall Franklin were born on November 16, 1934, just 24 hours after my last conference—at home—on A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” She was back at work in two weeks, adapting the gangster drama, Dr. Socrates (1935), before being loaned out to Columbia Pictures in 1936.

A Valued Writer on Set

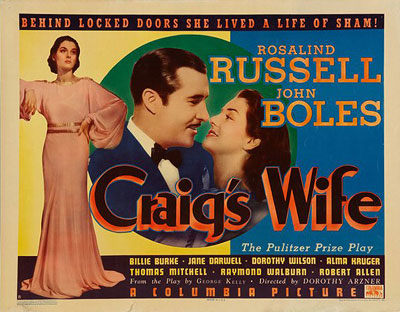

Mary Mccall, Jr. on the set of the film Craig’s Wife (1936).[From left] editor Viola Lawrence, Star Rosalind Russell, Mccall, and director Dorothy Arzner

Mary Mccall, Jr. on the set of the film Craig’s Wife (1936).[From left] editor Viola Lawrence, Star Rosalind Russell, Mccall, and director Dorothy ArznerBeing loaned out to Columbia was the best thing that could have happened to McCall. There she met two people who would change her attitude toward screenwriting and career independence: Dorothy Arzner and Harry Cohn. Arzner was Hollywood’s last remaining prominent female director. McCall would become her good friend and would speak at Arzner’s Hollywood retirement tribute a decade later. Arzner and McCall’s friendship came to fruition on the set of Craig’s Wife (1936).

Columbia’s production of George Kelly’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play about an acquisitive housewife was the studio’s top prestige film for 1936, intended to capitalize on and outshine Samuel Goldwyn’s Dodsworth, released the year before. Arzner wanted the best writing possible, and McCall’s former colleague at Warner Bros., Edward Chodorov, now a producer at Columbia, recommended McCall. As she remembered, “Miss Arzner’s belief that a writer should be a part of the making of a picture from start to finish, and that I had the makings of a good writer for the screen, encouraged me to stay [at Columbia].” McCall had been contemplating returning to New York given how “discouraged” she was at Warner Bros. merely drafting smart dialogue. She wrote the first draft, and then writer and director worked through each line.

“She questioned every move I made,” McCall remembered. “In the script, I would write, ‘She walks to the window.’ Dorothy would say, ‘Why?’ And I would answer, ‘Well, she’s getting the worst of the argument, so she is running away. She turns her back and looks out.’ ‘All right, all right, but I have to know why she moves. Otherwise I cannot direct it.’” McCall had a unique opportunity to shape the production and performances, because, unlike other directors McCall had worked with, Arzner “wanted the writer to be on the set.”

McCall told director Dorothy Arzner that working with her on Craig’s Wife, was “the finest weeks of my professional life.”

McCall told director Dorothy Arzner that working with her on Craig’s Wife, was “the finest weeks of my professional life.”Rosalind Russell was taking a career risk playing as unsympathetic a character as Mrs. Harriet Craig. But as film critic Mildred Martin wrote, “Craig’s Wife may give many women the thrill of recognizing themselves, not retouched…Miss Russell has stopped being a carbon copy—however charming—of Myrna Loy and has played Harriet Craig uncompromisingly and sincerely.” The film critic found it liberating that women dominated the film production (in addition to McCall, Arzner, and Russell, Viola Lawrence was editor). Martin took note of the fact that although a man (George Kelly) had written the stage play, the film was better because “only women could so deeply get beneath the skin of another woman and so devastatingly expose her.”

McCall frankly relished working with Arzner: “At the end of each rehearsal she would turn to me and say, ‘How is that for you?’ For the first couple of days I couldn’t believe it. I had never been assigned to a set before.” It was a true collaboration, and toward the end of production, they had a serious talk about McCall’s career. Arzner was worried that McCall would give up and return to New York. “When Dorothy asked me how this assignment had been, I said, ‘It’s been the finest weeks of my professional life. I have stopped the work reluctantly every night and have gone to it eagerly the next day.’ And [Arzner] said, ‘Well, it can be like that, you know, and you can make it increasingly like that if you stick with it. But if you turn your back on it and run away, then you will never have anything to say about how a motion picture is made.’” McCall took her advice, but knew she couldn’t remain at Warner Bros. as, in her words, a mere “corpse-rouger.”

At Warner Bros., McCall was on a rigid schedule. Salaries were low and it was the worst studio to work for if you were a member of the fledgling Screen Writers Guild—or a woman. Though her name was on several moneymakers, she was usually one of several contract writers on a project and preferred to work alone. As McCall remembered, of Warner Bros.’s 30 fulltime writers, only two were women—herself and Lillie Heyward.

In a speech at the Writers Guild of America West delivered in 1978, she shared the grim facts: “The average pay of screen writers equaled that of the body makeup men. Employees were bullied by the high brass—told, not urged, to donate campaign funds—given a list of films, players, directors to vote for in the Academy’s balloting… I collected signatures protesting the studio’s action. All the men who had signed it were summoned to Jack Warner’s office. He demanded to know what individual had written this. They all said, ‘We wrote it.’ But J. L., through native shrewdness and information from a fink, knew I was the culprit.” She was fired in the middle of Craig’s Wife, but Harry Cohn arranged to buy out the remainder of her contract so she could resume working for him straight away.

Cohn didn’t give a damn whether his writers belonged to the Guild or not; he didn’t care if they were male or female. What he cared about was good writing. One day as McCall walked across the Columbia lot on her way out, Cohn yelled out the window at her, “Where are you going?” When she replied, “I’m going to lunch,” he bellowed, “No one goes off the lot to lunch here.” “Well, I do, and I’m going,” she yelled back, and continued off the lot.

Any woman who yelled right back at Cohn had his respect, and as Mary said, “whereas he might break your jaw, he would never stick a knife in your back.” McCall remained at Columbia until 1938, when she made a well-publicized move to Hollywood’s richest studio, MGM. There she was right at home among some of the most famous—and female—writers in the business. Too at home, perhaps, for MGM’s executives. Because in addition to transforming Ann Sothern’s career with the sleeper Maisie franchise, she was signing up more SWG members, nailing down the producers’ contract, and, as the wartime president of Hollywood’s newest Guild, rolling up her sleeves to do battle with the Guild’s two new foes: the Motion Picture Alliance and the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Although the Screen Writers Guild had voted unanimously in favor of a contract on June 18, 1941, the producers wouldn’t officially sign for several more months. Writer Boris Ingster remembered executives Harry Warner and Paramount’s Y. Frank Freeman acting “insane” in meetings with the “very militant” board member Mary C. McCall Jr., who wouldn’t give an inch on the minimum wage and speculative writing clauses. “Is Y. Frank Freeman a rhetorical question?” she famously quipped.

During her presidency, McCall and Guild attorney Morris Cohen traveled to Washington, DC to negotiate wartime pay increases above and beyond the minimum wage (increases guaranteed by the contract). The industry-wide committee involved actors, producers, and writers. When producers proposed to go along with a potential five-year wage freeze, Mc- Call remembered, “I sucked air” and waited for “some of these handsome actors with good voices” to “come awake and say something,” but they “didn’t say a bloody word.”

So McCall stood and announced that, “The Screen Writers Guild could not go along with this because a contract is a two-way street and if one party, for any reason, is unable to fulfill his part of the bargain, the bargain is off.” The producers caved in the face of her threat, and were forced to ask permission to increase wages from the Roosevelt administration. This added another black mark to McCall’s record, as far as the execs were concerned. But, as she remembered, her writing colleagues “were pleased with me” and the Guild happily “draft[ed] Mary Mc-Call Jr. for a second term as president.”

During the war years, McCall was in the top tier of MGM writers, but the studio was getting its money’s worth at $1,250 a week (Maisie Gets Her Man, 1942; Swing Shift Maisie, 1943; Maisie Goes to Reno, 1944; Keep Your Powder Dry, 1945). By the end of the war, her salary had jumped to $3,000 a week. But McCall reaped even bigger rewards when she negotiated a landmark deal for The Fighting Sullivans (1944). For many years, McCall’s agent had been Mary Baker, formidable partner of the Jaffe Agency. When Sam Jaffe struck a deal with Twentieth Century-Fox for the Sullivan family story, he hired McCall at $15,000 plus a 5 percent share of the producers’ profits. Although writers such as Nunnally Johnson had won percentage deals in the past, Mc- Call shared her experience with other writers in an early issue of The Screen Writer Magazine: “I look forward to the time when such contracts will be usual.”

Meanwhile, McCall belonged to more committees than most writers had screen credits. She was not only head of the Screen Writers Guild, but also ran the Hollywood branch of the War Activities Committee, the Hollywood Democratic Committee (where she would meet and dine with idol Eleanor Roosevelt at Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas’ house), the Labor Management Committee, and several other political and charitable organizations.

At the War Activities Committee, McCall coordinated and commissioned cross-studio shorts, including a Tess Slesinger- Frank Davis script (What if They Quit?, Twentieth Century Fox), David O. Selznick’s nurse’s aide story (set to coincide with the release of the women’s homefront drama Since You Went Away, 1944), and RKO’s war-bond-drive short, Ginger Rogers Finds a Bargain (released by the Women’s Army Corps).

McCall’s two OWI/WAC film commissions for MGM, Box Office Maisie and Reward Unlimited, were also aimed at female audiences. Reward Unlimited, directed by Jacques Tourneur, focused on the Cadet Nurse Training Corps as part of a major recruitment push. Her Maisie short was tied to Swing Shift Maisie, the latest offering in her successful, never-say-die working-girl franchise, in which Maisie Ravier (Ann Sothern) takes a job in an aircraft plant.

Twentieth Century-Fox denied her credit for writing Marilyn Monroe’s dialogue in There’s No Business Like Show Business. With typically black humor, McCall quipped, "She needs dialogue?" takes a job in an aircraft plant.

Public Enemy and Private Heroine

McCall was an extremely popular Guild president. Prior to her election, she had been instrumental in getting the producers to agree to the first contract and also resisted pressure by left-wing elements to implement a writers’ wage freeze. With the producers still stalling on points of the contract, and the Guild threatening a strike in the winter of 1941-42, many of the Guild’s left-wing members advocated a freeze to show wartime solidarity—including McCall’s future vice president, Lester Cole. Moderate elements in the Guild were strongly opposed to what effectively was “freezing the contract” for the duration before anything had been formally signed.

When the producers offered the New Deal minimum wage of $125 a week before the freeze could be imposed, Cole, Dalton Trumbo, John Howard Lawson, and Ralph Block had, as Richard Maibaum would remember, “egg on their faces.”

Although McCall would publicly defend Hollywood against smear campaigns from outsiders (particularly in her response to Marcia Winn’s Chicago Tribune series in 1943), she continuously battled extreme right-wing political groups within the industry intent on muzzling the unions. Then, in the summer of 1944, she and her fellow Guild members were faced with a new threat: The Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (MPA). Sam Wood, president of the MPA, publisher William Randolph Hearst, and other conservative filmmakers began accusing liberal organizations and unions of “subversive activities.”

In July 1944, McCall and other prominent Hollywood Democrats launched a “counterattack” from the Hollywood Women’s Club, organized by the Emergency Committee of Hollywood Guilds and Unions. Fellow writer Oliver H. P. Garrett drew attention to the similarities between the MPA’s public statements and those of Hitler. McCall focused on the conservative attacks on Hollywood unions and “flatly accused MPA members of union-busting intentions.” She was widely quoted in the national press: “We don’t believe union-busting is an American ideal.”

The Emergency Committee united liberal workers across the industry that included the Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Screen Cartoonists, the Screen Publicists Guild, the Society of Motion Picture Film Editors, the Screen Story Analysts Guild, the United Brotherhood of Carpenters, the Songwriters Protective Association, and the Screen Writers Guild. Protection of the unions, a fundamental policy of the New Deal, was under threat. As attacks increased from the Hollywood insiders, such as director Cecil B. DeMille, Mc- Call counterpunched on the airwaves with her mid-Atlantic, Roosevelt-esque drawl.

In 1945’s Keep Your Powder Dry, (written by McCall & George Bruce), a young bride (Susan Peters), joins the WACs when her husband is sent overseas. She becomes an officer only to learn that her husband has been killed in action. She tells her girlfriends, “I just feel that right now, nothing’s important, except doing the best you can—whatever happens. Sticking to it. Not quitting. Lots of people—ordinary people—taking a job and not running out on it.”

This was McCall’s philosophy in war and peacetime with respect to her Guild, but the number of committees she belonged to or chaired was daunting even by her own standards. She was one of the most visible and vocal women in the industry.

Politics Gets Personal

Her personal life was just as complicated. In 1943, she had divorced Dwight Franklin to marry a younger man, army officer David Bramson. On August 4, 1944, Daily Variety noted that she had resigned as president of the Guild. But she was six months pregnant, and her condition had only recently become apparent. Was she forced to resign—a working mother of three, married, divorced, and now remarried to a younger man? Her longtime ally Charles Brackett was not able to take over for her as he was serving as President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. That left Vice President Lester Cole as the acting Guild leader.

Cole represented the Guild’s Communist faction, which was increasing attacks on the Roosevelt administration. Though McCall’s extensive Washington contacts provided the Guild some measure of protection from conservative Republicans and HUAC, Cole was not so skilled or well-protected a negotiator. He also resented McCall’s power within the Guild. Years later, Cole’s misogyny manifested itself when he described his election to the presidency as, “following the pregnancy of Mary McCall.”

Cole’s attempt to diminish McCall’s importance later in life revealed classic gendered resentment of a powerful woman. McCall had always inspired a range of emotions in her male colleagues, from antipathy and fear, to friendship and loyalty. Daughter Mary-David Sheiner later recalled some of her mother’s colleagues playfully addressing McCall as “Sir” on the phone and at meetings. Anti-Communist informants expressed their hostility a year later, in August 1945, when the FBI noted that according to one industry fink, “McCall had been active in Communist front organizations, especially those having to do with women.” While Mc- Call’s maiden speech as Guild president hadn’t been overtly feminist, her war work for the War Activities Committee and her scripts about working girl Maisie Ravier revealed her commitment to expanding women’s independence in the workforce— during and after the war.

Shortly before her resignation, as she led her colleagues in an attempt to defend the Hollywood unions from attacks by the newly-formed MPA, members of the Emergency Committee of Hollywood Guilds and Unions pledged to work with producers “in reabsorbing returning Hollywood servicemen and women.” McCall vowed this was one major industry where women’s employment gains were not going to be purged with the peace.

McCall Fights On

Despite her resignation, McCall returned to committee work and writing only a few months after the birth of Mary-David in November 1944. On March 2, 1945, The Hollywood Reporter noted that McCall had been elected chairman of the Council of Hollywood Guilds and Unions. She tactfully worked with the National Labor Relations Board to side with the radical alternative to IATSE, the strikers of the Conference of Studio Unions and Local 1421 picketing Warner Bros. It was a tricky situation, and not only because it split the left (the Communist Party members of the Guild were abiding by a wartime no-strike pledge and would not support the strikers). Had McCall and other trade unionists followed their first impulse and gone on strike with the CSU, the writers would have violated the Guild’s minimum basic agreement with the producers by siding with the other union. McCall could sense the danger to Hollywood’s labor movement through right-wing efforts to smear New Deal liberalism with Communism. FBI informants reported that in the period since she resigned the presidency, “there had recently developed…considerable opposition to the pro-Communist leadership.”

Her friend Emmet Lavery assumed leadership of the moderate majority in the Guild, and took over the presidency in 1945, with McCall later serving as his vice president in 1946-47. To an extent, McCall was his mentor, and they shared a commitment to the Guild that trumped any political alliance. Things would stand or fall for them, not over HUAC’s disputes with the Hollywood Ten, but over the threat posed by the Taft-Hartley Act (1947).

Briefly, however, writers across party lines united to mourn the death of Franklin Roosevelt. The Roosevelt administration’s labor policies were responsible for the Guild’s victories in securing a contract, and McCall, like her close friend Bette Davis, was a conspicuous supporter of Roosevelt in the 1944 election.

In the spring of 1945, MGM producer Dore Schary wrote to the secretary of the Hollywood Writers Mobilization, Pauline Lauber, asking McCall to write a speech for an FDR memorial program at the Hollywood Bowl. Helen Deutsch, Lavery, Francis Faragoh, Ring Lardner Jr., Dalton Trumbo, and McCall were among those members approached to write speeches. (Two years later, this speech put her under scrutiny for Communism; Jack B. Tenney’s California Legislative Committee investigating un-Americanism, claimed that the Hollywood Writers Mobilization was “100 percent pro- Communist controlled.”) Although never specifically under investigation by the FBI, McCall’s file, opened when she was elected president of the Guild in 1942, grew with her anti- MPA work—in spite of the fact that she did not belong to the Committee for the First Amendment, and refused to publicly support the Hollywood 19 or other calls for the Screen Writers Guild to defend the Hollywood Ten. She did, however, continue to support the rights of unions, speaking in March 1947 at Los Angeles’ Olympic Auditorium in protest against the recent “attacks on labor.”

Over the summer of 1947, political tensions exploded: 43 names were added to HUAC’s list as it opened investigations into alleged Communist infiltration of Hollywood. Some were friendly witnesses; others—many of them screenwriters— were not. Ten would be cited for contempt of Congress and were given year-long jail sentences.

The issue for McCall was not saving a few screenwriters from jail, but the survival of the Guild itself. The Taft- Hartley Act stated that labor union leaders had to sign affidavits proclaiming their non-Communist affiliation or lose the protection of the NLRB in labor disputes. Furthermore, should disgruntled members on the right break away from the Guild, angered at any gestures of protection for Communist members, Taft-Hartley would encourage them to break the power of the writers’ hard-won union. Only those non-Communist-declaring groups would make the ballot for a new union, so outraged members of the left fleeing the Guild would have no protection at all and couldn’t even be eligible on a ballot. Should the Guild members not declare themselves, then the Guild itself couldn’t even be on the ballot. Writers would be back to the days of the Screen Playwrights, when no contract existed and secretaries were paid more than screenwriters per week.

This was why McCall and past presidents had safeguarded the political affiliations and names of Guild members. She, Lavery, James Cain, and other members of the Executive Board, offered to sign loyalty oaths—eventually filed with the Guild—that they were not Communists, as a way of protecting the rest of the members. The alternative, they felt, was the loss of the Guild’s legal status as a union and everything McCall had fought for to obtain the contract. Lavery asked rhetorically in 1948, “Is it too much, under all these circumstances, to ask our brethren of the far left to sit out one waltz? To give the Guild every chance to protect itself in the event of another bargaining election? To put Guild policy, for a few months, or a year perhaps, above one’s personal political policy?” It was a question of temporary “strategy” to keep the wider gains of the Guild safe, he argued. However unconstitutional Taft-Hartley was, it had been approved by Congress and was now the law of the land.

Soon after, Lavery and McCall stood down from the presidency and vice presidency, worn out by the thankless task of being moderates in the middle of a political shooting range. They continued to maintain a foothold in industry politics, running again for the Executive Board in 1948 along with a suite of other moderate writers, including Jane Murfin.

In 1951, still in the throes of the blacklist, Guild members elected McCall to take over its leadership a third time. However, her final term in office was marred by a credit dispute with the head of RKO Pictures, Howard Hughes, nephew of her old adversary on the MPA, Rupert Hughes. Guild and Communist writer Paul Jarrico had signed a contract with Hughes for The Las Vegas Story (1952) and was denied final credit due to his political affiliation. Hughes’ action was in violation of a fundamental right of the Guild, won in 1941-42, to arbitrate and award screen credit on all productions. McCall defended Jarrico. As she remembered, “I did not intend to permit Mr. Hughes to trample on a labor agreement with muddy tennis shoes.”

Anti-Communist informants expressed their hostility a year later, in August 1945, when the FBI noted that, according to one industry fink, “McCall had been active in Communist front organizations, especially those having to do with women.” While McCall’s inaugural speech as Guild president hadn’t been overtly feminist, her work for the War Activities Committee and her scripts revealed a commitment to expanding women’s independence in the workforce.

She sent Hughes a letter stating that RKO was in breach of the Guild contract and that, “This is clearly a labor dispute. It does not involve the political beliefs of Mr. Jarrico, however repugnant they might be to you or us.” He and RKO took the case to court, and predictably, the Guild lost its case and the right to appeal to the California Supreme Court. By 1953, the contract McCall had fought so hard to secure was rewritten to deny screen credit to Communists. But by then, she had resigned. Her career was over. To add salt to the wound, Twentieth Century-Fox denied her credit for writing Marilyn Monroe’s dialogue in There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954). With typically black humor, McCall quipped, “She needs dialogue?”

The Mary McCall Case for Hero Status

To her dying day, McCall believed Hughes gave her name to his FBI contacts and had her blacklisted. Yet, Hughes should not receive sole credit for blacklisting McCall. It was her long-term commitment to the writers’ union, her willingness to take stands, strategize, and compromise that ultimately ended her career in Hollywood. Listed in Red Stars in Hollywood as a fellow traveler in 1950 by Myron Fagan, and facing poverty in the summer of 1951, McCall wrote directly to J. Edgar Hoover, stating that she was “against both Communism and Fascism and was for Democracy.”

Together with Sheridan Gibney, Charles Brackett, and Lavery, she claimed she was “among the middle-of-the-road people who believed sincerely in the principles of collective bargaining and craft unions, and who were willing to take the boredom and hard work of attendance at Guild meetings and of office-holding in the Guild.” Hoover responded personally but unhelpfully, stating that she was not a subject of any investigation and should “use your own good judgment” as to how to proceed with employers. McCall was out of the industry and virtually penniless. In the hope of getting assignments in television, she even testified before the California State Committee in 1954, refusing to take the Fifth Amendment, stating baldly that she “hated” Communism, but declining to name names. The committee heard and exonerated her, the FBI acknowledged that she was not a Communist, and the press in Hollywood and nationally gave her sympathetic coverage.

But producers who had once made hundreds of thousands of dollars on her scripts continued her blacklist status.

McCall scratched out a living in the television industry, but several years later she was still being targeted by Fagan’s rightwing organization. In the California Legislature’s 11th report of the Senate Fact-Finding Sub-Committee on Un-American Activities, members discussed “The Case of Mary McCall” as a separate item. The committee members agreed with her criticism of Fagan and his ilk, deploring this particular manifestation of witch-hunting. Daily Variety went out of its way to exonerate her, but still Hollywood producers did not offer her any pictures. In 1960, after a 10-year hiatus, Hollywood would put Dalton Trumbo’s name on Spartacus (based on the novel by Howard Fast), but McCall—outspoken woman, political moderate, and defender of the Hollywood studio and guilds systems—was not an appropriate “hero” for the postblacklist era.

She was not a Communist, and pulled no punches in her dislike for Guild members Lillian Hellman and Dalton Trumbo: “My own feeling about persons who shout their virtues and disclaim their sins of which nobody responsible has accused them, is that they protest too much. And my feeling about members of the Communist Party is that they would not hesitate for a second to lie under oath, except when they know there’s enough evidence in the hands of the investigators to convict them of perjury. Under those circumstances, they prate about the First Amendment, or run for the border.”

Unlike Hellman and Trumbo, McCall respected and had publicly defended the Hollywood studio system, and had pledged herself to work within the industry to improve basic working conditions for writers and all members of the guilds and unions. Although it is perhaps understandable that producers would want to destroy her career in revenge, historians’ and critics’ marginalization of McCall in the history of the studio era and the Guild is more unsettling.

As she used to say, “When the revolution comes, you can put me up against a cellophane wall and shoot at me from both sides.”

J.E. Smyth’s Mary McCall research is featured in her book Nobody’s Girl Friday: The Women Who Ran Hollywood, from Oxford University Press.

(This article was originally published in June 2017 as a Written By web exclusive and in the September 2017 issue of Written By.)