AAPI writers tell stories about telling their stories.

9/5/2025 • Jack Giroux

How to Stay Motivated When Jobs Are Scarce

Red Sonja writer and Act Two Podcast host Tasha Huo advises writers on how to keep going in challenging times.

WGAW’s Asian American Writers Committee (AAWC) has had much to celebrate since its inception in 2002 including a growing number of Guild members who identified as Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI). AAWC Vice Chair Tracy Held joined in 2017, when there were about 20 members who self-identified as AAPI to the Guild.

That number rose to about 80 before the pandemic. When meetings switched over to Zoom, committee members found themselves facing more than just fears about Covid. Inflammatory anti-AAPI rhetoric from public figures fueled a spike in hate crimes against AAPI people across the country. With the ensuing #StopAsianHate movement, Held (Conservation Starters) says “it was clear that this was the opportunity for people to raise these concerns in public. And it provoked a lot of other concerns about what it’s like being Asian in the industry.”

The committee hosted events to reach out to the community. “We had a panel called Stop Asian Hate, and we co-produced a panel with the Writers Guild Foundation as well,” Held says. “There was a lot of conversation inside and outside of the Guild that highlighted a lot of concerns that are mirrored in other communities as well, but this was the first time as a community that Asian writers were focusing on this.”

The AAWC now boasts 250 members. “There’s not just a dozen of us, and that’s exciting,” says Chair Kristina Woo (Halston). “To be able to talk to people at all levels, across television and film, and to hear from people going through the same things that I’m going through, has been really gratifying.”

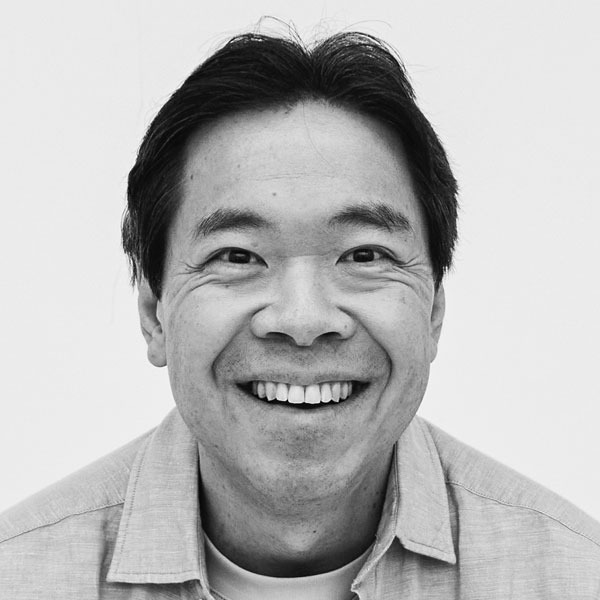

In April the committee hosted a meeting which 3 Body Problem co-creator Alexander Woo attended as a guest. “It was so fun because people could chat, get to know each other,” says Kristina Woo, of the committee’s first in-person event in four years “I met a lot of people who I’ve only seen on Zoom. Having that person-to-person connection is really important.”

Written by spoke with a small group of AAPI writer-producers about strides and setbacks in representation and persevering in the face of today’s uncertain landscape.

Strides and Setbacks

A Guild member for 21 years, Alexander Woo didn’t work on a show with AAPI characters until co-creating The Terror: Infamy, about the internment of Japanese American citizens, which aired in 2019. “This was the opportunity for the first time to tell an Asian American story, and…one of the biggest ones, with over 100 people involved in the production who had families who were in the camps, or were, in the case of a couple of actors, in the camps themselves,” Alexander Woo says.

“My perception is that there seems to have been, in the last few years, more interesting AAPI content that depicts Asian and Asian American characters more three-dimensionally than it has in the past, warts and all, which I appreciate,” he continues. “Beef is an obvious example.” But in the wake studio mergers and production contractions, “less stuff is getting made across the board.”

“Oftentimes the first things that get taken off the list are things that are considered even the tiniest bit risky,” Alexander Woo adds. “So I’m not sure that in this particular climate, today in 2024, some of the things we’ve been celebrating in 2022 and 2023 might get greenlit now.”

Awesome Asian Good Guys

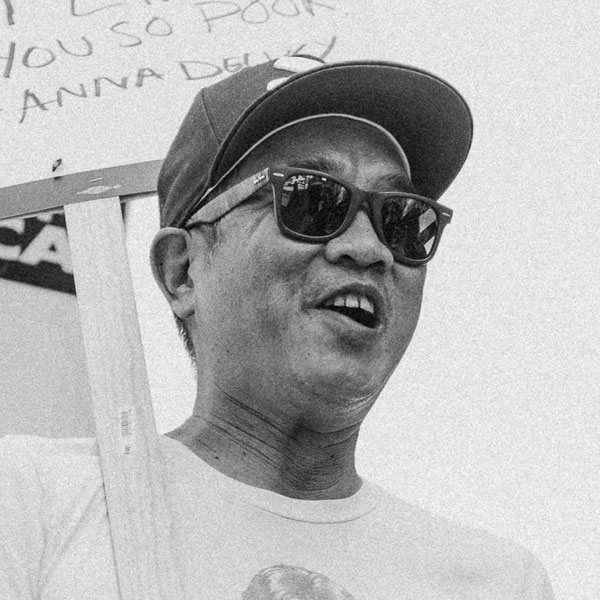

WGAW member Milton Liu (Awesome Asian Bad Guys) is Executive Director of the Asian American Media Alliance and has been involved with Visual Communications, producer of the Los Angeles Pacific Film Festival, since 2012. He’s deeply aware of the realities of AAPI inclusion in front of and behind the camera for the past 12 years. It doesn’t look good.

Liu cites the STAATUS Index Report, an annual survey from The Asian American Foundation. “They poll Americans: Name one famous Asian American,” Liu says. “Over 50 percent said, ‘I don’t know,’ and the leader for the past four years with nine percent is Jackie Chan, who’s not American.”

I just know that for my AAPI community, we have to keep creating, keep writing, keep making shorts, keep doing things that are not traditional, because as artists that’s the only way we can satiate our crazy brains.

- Milton Liu

Every one of his projects has an AAPI lead. “How many times have I been asked, ‘Does the lead have to be Asian?’ And the show’s called Tina Chang goes to Hell,” he notes drily. “There are all these kinds of microaggressions, which really mean, ‘We can only have one Asian project.’”

Representation isn’t even a matter of appealing to CEOs’ better natures—it’s proven to increase their bottom line. “The Hollywood Reporter just came out with an article that Hollywood is leaving $30 billion on the table by not having diverse casts,” Liu says.

Liu doesn’t profess to have the answers to such systemic problems: “I just know that for my AAPI community, we have to keep creating, keep writing, keep making shorts, keep doing things that are not traditional, because as artists that’s the only way we can satiate our crazy brains.”

Taking the Reins

“We sometimes forget how recently things were pretty terrible,” says Kelvin Yu (American Born Chinese).

When he started out in the industry as an actor in 2001, “my first role was a high school nerd on the show Popular—there was nothing subtle or nuanced about it. For years I paid my rent as a repressed Asian husband who would murder his wife because she looked at another man.”

Unable to make a living as an actor, he turned to writing. Yu now has a deal with Disney, and is preparing to take out a half-hour network comedy about an AAPI family that owns and operates a golf course in Hawaii.

He recognizes the barriers to entry are difficult to navigate, “but I don’t lament it a lot. As an actor you wake up in the morning and just hope that things have changed. When you write, that circle of control is within your hands, so you can influence how the industry does that, you can make that thing that pushes the needle. That’s how I try to give myself agency.”

Broad Appeal

Think Tank for Inclusion and Equity (TTIE) has used focus groups and detailed surveys to turn anecdotal experiences of historically excluded writers into concrete, sharable data. Co-founded by WGAW members Y. Shireen Razack and Tawal Panyacosit Jr. to assist and advocate for TV writers, TTIE’s work includes programming, consulting, and extensive fact sheets. Instead of one AAPI fact sheet, they look at four distinct communities: East Asians, Southeast Asians, South Asians, and Native Hawaiians & Pacific Islanders, delineating stereotypes and offering fresh storytelling ideas.

“What we have tried to do with those particular fact sheets is to teach writers that not all Asians are the same,” says Razack, who’s also captain of TTIE’s research committee. “#StopAsianHate was very much impacting East Asians, Southeast Asians, and Pacific Islanders, but didn’t really impact South Asians. But South Asians end up getting impacted whenever something’s going on with terrorist stuff; it’s a whole different set of issues. The primary goal of our fact sheets is to make sure there’s proper representation, and to make sure that writers understand what the differences are.”

A recent TTIE panel offered strategies for dealing with today’s contracted climate. “One of the things that was said to the writers was: Before you go into the pitch, know that you’re going to have to make the case, prepare for it, there is nothing that says a character of color doesn’t have broad appeal, but you may have to connect those dots,” says TTIE Program Director Maha Chelhaoui.

Adds Razack, “The thing to drive home is to pitch it as: This is what will connect with audiences. This is the broad-appeal theme; this is the broad-appeal storyline. Never Have I Ever has a South Asian lead, but everything that she’s going through is completely relatable to young adults in every way. It’s not just Asian people who made Crazy Rich Asians make as much money as it did. These stories have broad appeal; they just don’t have white stars.”

The Community of Committees

Held invites everyone to join an AAWC meeting, and also encourages people to check out other committees’ programs. “The more I listen to people from communities other than mine, the more I realize we’re all actually facing pretty much the same stuff,” she says, “but when we’re made to feel like we have to silo into our own demographic, then sometimes we think we’re the only ones, and that doesn’t benefit anyone except the people who have control over us and our jobs and the stories that get produced.”